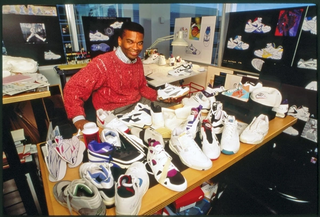

Nike Air Flare. Air More Uptempo. Air Max CB34. Air Jordan 17. These are just four of the dozens of iconic sneaker designs credited to Wilson W. Smith III, a formally-trained architect who spent 41 years at Nike, Inc. developing footwear for the likes of Andre Agassi, Serena Williams, and Michael Jordan.

A product of the Pacific Northwest, Smith, now in his mid-60s, joined the Swoosh during a pivotal time, though his earliest role was in Corporate Architecture under the supervision of Tinker Hatfield. The transition from traditional building design to athletic footwear wasn't all that difficult for Smith—after all, he considers shoes "homes for the feet"—but it was ground-breaking as it made him the company's first Black sneaker designer. Internal restructurings, a rotating cast of athlete endorsements, and personal pursuits took him across a number of roles and teams during his decades-long tenure with Nike, Inc. Wherever he went, Smith was guided by an eight-word phrase: "...in humility count others more significant than yourselves."

Fast-forward to today, the U.O. alumnus still resides in Oregon, but has largely stepped away from the seasonal grind of footwear design to focus on supporting the aspirations of and work by newer "sneaker architects." To this end, Smith works with the Nike Department of Archives (DNA); assists design professors at his alma mater; and regularly collaborates with creative platforms and people to share insight—including the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD).

Smith was one of the university's invited guests for its SNKR Culture Week 2025. In the aftermath of the event, the former design director sat down with House of Heat° for a 110-minute video call through Zoom to discuss jazz-inspired Air Jordans, how today's Nike compares to the past, and the legacy he hopes to leave.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

House of Heatº: You officially retired from Nike, Inc. in January 2025. How does your day-to-day look like now?

Wilson W. Smith III: I started out in architecture, then I was a footwear designer and I kind of moved more into being a storyteller. So, a lot of what I'd be doing would be inspiring teams and storytelling. I was doing that out of Nike DNA, which is actually the Department of Nike Archives. Now, it feels like I've transitioned almost to where I'm really busy doing similar kind of work outside of the company.

I'm also doing some educational things. I'm working at the University of Oregon, supporting a design studio focused around adaptive design that enables athletes with disabilities, which is pretty cool because this is an underserved community.

You know, I've got a couple of projects that I'm doing on the side—still with athletes. I'm working on a book design with an athlete, a book that kind of talks about his first signature shoe or something. Um, I'm trying to think what else am I doing? Let me think. You know, hopefully inspiring the next gen is kind of what I'm really kind of into.

Let's touch on your work with Nike DNA: Why is preserving history and even being part of something like a campaign for the Infinite Archives x Air Jordan 17, a shoe you designed over 20 years ago, important to you?

Oh, cool. That's a great question, Jovani. You know, I, I think it's all about the stories. Shoes themselves are great, but shoes are kind of almost nothing if there's not a story there somehow.

You know, I studied architecture in school and architecture is very much about context: a building, where it's sitting on the site; what's next to it; where the sun moves; just everything about it. For me, you almost gotta kind of know where you've been to help define where you're going.

I think if you're having dialogue with a customer or person buying into your brand, it's good for you to know previous dialogue and then build on it or duplicate it if that's part of what needs to happen. These stories are really rich because you can incrementally evolve and change them.

Do you think that brands sometimes rely on the past too much?

Well, you definitely don't want to be one who looks back too much, but, you know, inspiration matters. If something was good, it's okay to do it again, but not just retroing the same old vibe.

A big topic of conversation over the past 18 months has been this idea of Nike and Jordan Brand relying on their big franchises, which I think is worthwhile dissecting.

No, I hear you.

I think back to the biggest eras in sneaker history and believe a lot of greatness came about because competitors were doing a great job. As consumers, we can’t help but notice that maybe Nike has something to prove again.

I think the interesting thing about the past is that shoes didn't really start mattering in the way they were designed or expressed, really, until the Air Jordan. Fall of ’87 is what I call the renaissance of the whole thing because that's when Nike Air Max, the Air Trainer, Air Safari took off. After that, when you go into the '90s, you have an industry that's kind of awakening in terms of materiology, manufacturing processes.

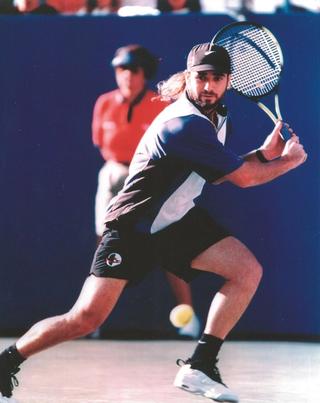

People sometimes call the ‘90s the “golden age” of product design and it’s because the industry was blasting off in the way it expressed things. We won’t necessarily see some of these things today–like some of the Andre Agassi stuff—because we’ve evolved from that era.

The pervasive design leader today is maybe Apple. Because they are kind of everywhere, everybody's kind of adopted their aesthetic to some degree. What they represent is a very simple, understated, clean design. This aesthetic, I think, has informed everything—including a lot of shoes.

When shifts like that happen—let’s say in the months before Fall ’87—are there internal conversations as to what Nike Inc. wants to look like? Are they dictated by developments to the degree of Air Max?

Hmm, interesting. Well, I would like to think it was that scientific.

I was hired by Nike to do architecture. Tinker Hatfield was the Corporate Architect and I was his assistant. We were doing brand stories through architecture. Tinker designed this store in Westwood [Los Angeles] for the '84 Olympics where a giant swoosh “crashed” into the building from outer space. The project had all this energy. Basically, the same energy was later applied to footwear.

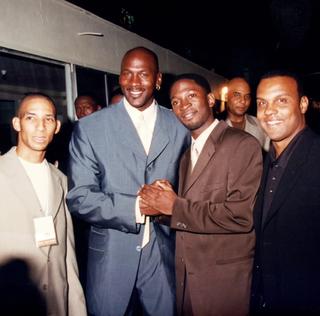

In ’85 or so, women’s aerobics took off. We didn't really take it that seriously, but Reebok did and they shot up in market share. We thought “Nike is about athletes,” and so, that was part of the motivation—we were gonna tell stories around athletes. One that people fell in love with was Michael Jordan. This guy was flying through the air. You look in LIFE Magazine and it’s pretty amazing. Being inspired by that image, you say, “Hey, we could tell a story around this athlete.” In a sense, that's gonna be our brand. Michael really played such a key role, so then we started really looking at sports stories and cross-training. We basically identified our strength—which was in working with athletes—and, now taking our explosive expressiveness like a swoosh crashing in the front of building or whatever, applying it to product design. So, when you see things like [Tinker’s Air Max 1], that was such a big deal for us because that was telling a story visually and in product.

Would you say that some of the brand's lulls can be contributed to it distancing itself from that athlete-first storytelling?

Right. I can give a guess because I don't know all the factors.

You know, COVID-19 was a little bit of a hurdle in terms of the way we connected to our customers through retail. We probably put too much emphasis on our online channels when COVID happened. At first, we were really quite successful. There was also a little bit of neglect towards our retail partners, so when they filled up their walls with product, Nike was no longer in those spaces the same.

Some of the other hurdles that we've faced, I'd say, is that we may have gotten away from enough authentic programming of products. I think Nike is strongest when we're doing what we're about, which is being inspired by athletes. Even when product is initially worn on-the-court and then goes into a streetwear place, it comes from a source of authenticity. Starting in a Sportswear place doesn't have as much inspirational authenticity as starting on-the-court. Look at something like the Ja 3 or the, um, what's his name? Shai [Gilgeous-Alexander] shoe at Converse. That shoe's gorgeous. Everyone knows it's SGA's and he happened to have won the [2025 NBA Championship], so that's a nice point. That shoe will forever have some good meaning to it because it's based in authenticity and performance. I think that if we had thrown the [Converse SHAI 001] out there without any kind of connection, things would look differently.

Everything you mentioned can be seen in what Nike Running has been doing over the last 10 months. I think something like the Pegasus Premium could have launched through Sportswear with a nice marketing package and worked, but educating people on the fact that it’s a high-level performance product that also looks good has been important.

It's been interesting to observe. Because of my work in DNA, I've tried to understand who we are. That's not to say that you ever box things all in; you know, just when I say all this, maybe [Nike'll] come up with a Sportswear line that's totally legit—and that's just fine—this just hasn't necessarily been who we are as a brand.

Staying with Nike Running, were you aware that the Vomero Premium has similar Air branding to the Air More Uptempo you designed?

Oh, man. Well, that's very honoring that you would connect those two. I'm certainly a big Vomero fan. Yeah, no, I love it. When I saw that, I was going, “Wow, I’m so excited that that still resonates.” It’s such a joy to see.

It’s funny; I remember the first time the marketing guy [David Bond] says to me, ‘Write the word Air as big as you can on the side of this [shoe you’re working on],’ I was like, “Okay…” He took something I was doing, flipped it over, and wrote “Air” on it. When we first did that, I realized the letters could be flipped on the inside or outside of the shoe. I thought, “Wow. It seems like this could have legs,” but, it’s really up to the consumer.

At the time, I went to show Tinker the sketch and said, “What do you think?” He was like, ‘Number one: it’s bad design. Number two, you’ll sell millions.’ He was looking at [the Air More Uptempo] as a purist a little bit. When you think about it culturally or within the context [of the mid-‘90s], the shoe was a different kind of thing. Scottie Pippen really liked the shoe because he felt it really expressed him bursting out—kind of exploding into a new, larger-than-life [role as a point-forward].

I'm based in Mexico City now, but originally from New York.

You're there right now?

Yes. Originally from New York—the Bronx, specifically.

Oh, cool.

One thing that I love to do whenever I'm somewhere is look at footwear people are wearing. The Air More Uptempo is one of the more popular shoes here. I didn't understand why, but I've come to learn that many people—especially those in the city's underground music scene—connect with its boldness.

A quick thought: I think one thing that's helped the Air More Uptempo's retro run is, as long as the prevailing wind of aesthetic is very clean and understated [à la Apple], there are gonna be times when people will want to wear something outrageous and outlandish. People don't always want to be understated.

Returning a bit to your origins at Nike: How were some of your earliest years navigating the industry as a Black designer? Is mentorship something you sought out?

I was very fortunate at Nike because Tinker was the Corporate Architect. I meet him and I immediately loved his work, the way he thought, the stuff he was doing. I was like, "Man, this guy's really dialed in." I could tell he was the kind of person that I would want to be mentored by. He actually didn't hire me right away, but I bugged him for like 15 months until he finally did. I had gone to work in city planning and a bunch of different things, but I [wanted to work at Nike] because I really enjoyed the vibe.

Even though I had these lofty architectural thoughts [as the self-proclaimed "Frank Lloyd Black"], there was something cool about a corporation that gets after it faster and quicker, kind of in and out. That whole energy, it reminded me of almost, say, Andy Warhol.

Tinker was my primary mentor at the time. By late-'84, he had started doing a lot more shoes. I would just watch him because I'd sit right next to him, but I was never personally inspired to do shoes. They called me to [a meeting] at the end of '86 during a layoff period and I thought, "Oh, boy, I'm gonna be let go." There, they said, 'How'd you like to design shoes?' and I was like, "I always wanted to design shoes!" although I'd never really thought of it. Driving home that day, I remember thinking, "Oh my gosh, what's happened to my career? I'm this highfalutin thinker of architecture, not designing shoes."

By Fall '87, some of my shoe designs—the Nike Outbreak and others—are starting to appear [at retail], so I'm having fun. I'm just as excited as if I was doing some amazing building, and maybe, arguably, more satisfied because you can get in-and-out of a shoe a lot quicker than a building. And then everybody's wearing them, so it's a very gratifying world.

Other people at Nike that I've always respected include Howard "H" White [Senior Vice President, Jordan Brand], Mark Parker, who was also my boss and eventually becomes CEO, Peter Moore [designer of the Air Jordan 1], and some of my colleagues like Eric Avar [of Nike Basketball fame].

Around ’97, Howard and Tinker came to me and said, ‘Hey, we’re gonna start this Jordan Brand and we'd like you to be the first dedicated designer.’ I remember thinking, “A Jordan Brand?” I had been kind of leading the charge at Nike Tennis, working with Agassi, Pete Sampras, Monica Seles. We would always do sub-brands that would do okay for two or three years, but then we’d drop them. So, I thought, “I’ll go do [Jordan Brand] for a while then just leave the company.” I didn't think it was going to be much, but that takes off.

You spearheaded both the Air Jordan 16 and 17, correct?

Yep.

How far out from these models coming out to the public were you tasked with developing them? How did you, 1. Prepare to go into such projects? And 2. How did you stay or return on course during design processes to ensure deadlines were met?

Okay. So, typically, for almost all models, it's about a 15 to 18-month process. You may spend a couple months kind of trying to get the concept together, get it approved, and then you start the 3D-building process and modeling it. By the time you get to about six months before release, you will have the sales meeting. The last six months are about getting [the shoe] made and everything.

If I'm working on the [Air Jordan] 16, which came out in 2001, and the [Air Jordan] 17 came out in '02, I'd have been designing them around the turn of the 21st century.

We have a room at Nike DNA—the Basketball Room. You walk in there and see all major models throughout the history of Nike, all in one room. It's kind of amazing; they’re all in chronological order, and you're just like, “Wow!” You're looking at all this story and model design. When you come up towards the end of the '90s and into the 2000s, it's interesting: suddenly, you see a whole lot of new chances taken in terms of closure systems. There is just a lot of evolution of the way we close shoes—whether with straps or overlays. It's almost a futurism that's kind of happening in ’99, 2000, 2001, 2002. After that, we go back to a sea of laces again. The Jordan 16 and 17 were of that era.

For the 16, the story was that Michael was moving from the basketball court to the boardroom—you know, he had retired for the second time. The shoe had a spat over the top of it. So, the whole idea of the 16 was something you could wear with a tux or whatever; you could take off the spat and you'd have the performance sneaker underneath.

The 17 was really inspired by looking at music. Music became a strong inspiration because, what happened was Michael—the 16, Tinker and I worked on, but, but he started it a little bit—but the 17 was just me. I felt a little bit of pressure and I was trying to figure out who I was. A friend of mine said to me, ‘You're much more influenced by the people who believe in you than even the other people who you believe in.’ I thought, “That's pretty cool.” People like MJ or Tinker believe in me to do [the Air Jordan 17] so I thought, “just do this thing.” As a designer, I was like, “Okay, I gotta design a shoe for the greatest guy ever, but how can I relate to the greatest guy ever?” At the time, Michael was investing in Hidden Beach Records and I thought that was pretty cool because I'm way into music—my dad owned a record shop when I was growing up. “I'm a music guy,” I said. If I'm inspired by music, that may help us get to a place that tells a story.

Hidden Beach is a jazz label. I heard a guy on the radio saying that the thing that separates jazz from all sorts of music was improvisation. When he said that, my mind just exploded. I was like, “Oh, great! Improvisation is what I'm looking for.” You know, Michael's the master improviser on a basketball court. The way the guy talked about improv was, the band lays down a rhythm and you improvise over the top. Well, Michael had steady fundamentals to his game, developed over his career, that he can improvise over depending on how defenses are. So there’s a story of improvisation as it relates to the game of basketball.

Then I thought, “What does that mean for the shoe?” We were trying to get after a better-fitting product, so we thought in some level of personalized fit. There were multiple ways of lacing the [Air Jordan 17] on the sides and through the mid-foot; you could also wear it without any laces and just have that lace cover on. Improvising the fit was really the thought there.

That whole [jazz] story was really pretty strong. It helped lead the direction of the shoe. When Spike Lee was working on the shoe’s commercials, he was inspired by Blue Note Records. Everything about the shoe played off of that jazz story.

The [Air Jordan 16 and 17] were the two hardest things I think ever did. We went through all kinds of very, very, very arduous, challenging product creation processes because you're trying to do something that's never been done before. I was following up Tinker, who had done the [Air Jordan] 3 through 15, which were insanely over the top. I was feeling a lot of pressure, but, once again, that empowerment thing, you know? They believed in me.

Shifting gears a bit: You spoke at the Savannah College of Art and Design’s SNKR Culture Week in October. Speaking with students, did you get a glimpse of something in particular that seems to be on the mind of today’s aspiring designers?

Hmm. You know, they kind of double clicked on meaning. When I say meaning, I'm thinking, they don't just care about the “what,” they really care about the “why” behind the “what.” They care about the environment, about what you're doing to support the ecosystem.

We did a project with the SCAD students around tennis and a lot of them really gravitated towards Naomi Osaka. Her story is pretty interesting in that it’s kind of that, “look good, feel good, play good,” but also about the psychology behind some of why she wants things [a certain way]. She kind of tries to create a place that's peaceful. Many of the students picked athletes or stories that were meaningful, like healing or something; they weren't as much excited or motivated by style or expression, but by something that's going to really help [people]. I hadn’t really seen that before.

I imagine this has to do a bit with what's going on around us. Since COVID, things have been a little trying for many of us, you know?

Yeah, absolutely.

I've watched trends: when we were coming out of glam [of the '70s], we went into grunge [in the '80s], which was something much more real. It seems like each successive generation is a little more aware, a little more conscientious and wants to explore new ways of helping [others].

Speaking of conscientious designers, Virgil Abloh is someone who comes to mind. Like yourself, he didn't have a traditional path into footwear design. Could you speak about him a little bit? Did you ever work together?

He remains such an inspiration to all of us. What he did with Nike’s [The Ten in 2017], he was really great at getting us to be a little bit bolder.

In 2018 and ’19, Virgil designed Serena [Williams’] amazing outfits at the [U.S.] and French Open. They were just brilliant because he was thinking about her motherhood, telling stories with what she was wearing. It was powerful.

You know, when we first signed Serena in 2003, we were getting ready for the U.S. Open. We had these 4 by 8 boards that we would cover with a bunch of torn sheets from magazines, and colors and materials, that were applied to various stories. Serena herself was virtually a design director. What she wanted for the U.S. Open was like jeans, urban stye, sexy. We were gonna do a head-to-toe look for Serena for the first time just 10 months after we had signed her.

At the time, I asked Mark Parker, who was the Design Director, “If you were designing for Serena, what would you do?” He said, ‘Well, I would let her sense of fashion and style lead the innovation. Don't just innovate and expect her to come on board.' With that in mind, I asked her, “What do you think about a tennis boot?” She loved the idea so I showed her a sketch and she signed off on it. I went to the Nike Innovation Kitchen to ask about designing a tennis boot. They [gave me the idea] to treat it like a compression sleeve that you can warm up in, or something that would be a good thing for blood circulation. Serena could zip it off or whatever.

When it came time for the U.S. Open, we were doing what Serena wanted. She wanted “rebel with a cause”; she wanted leather, studs, and all this stuff. The shoes [the Nike Shox Glamour SW] had this boot over the top, which was not unlike the [Air] Jordan 16 I had just done. Anyway, Serena comes out at the Open, and it's like she's on a Paris runway with all the cameras flashing. People at the Open didn't really like it; they didn't want this much expression. She zipped off the boots and crushed her opponent [Sandra Kleinova] that night. It was great. Later, some of the first images on SportsCenter were of the boots. The next day, a picture of the boots was on the front page of USA Today.

Virgil was really good at bridging sport and street, and in some ways, I think Serena was one of the athletes that helped us get there, that helped us express that.

When it's all said and done, how would you want your legacy to read?

Oh, man, I would hope it says that I was able to inspire and pass on to the next generation. At this point, that's really what I want to do more than anything else.

I've had the opportunity to tell my story, hopefully in an inspirational way. So, I want to empower the next gen to be able to believe in their era, their story, and their opportunities—to flourish in that.

You know what? I just thought of one more thing—there’s always one more thing. [There’s a special Air More Uptempo] that basically tells my story. Nike asked me for a quote to put on the shoe and I gave them this one, “…in humility, count others more significant than yourselves.”

I think that if we, as a culture, a people, propped up others, we'd all be taken care of. The diversity of all of us is like our human superpower. So that’s what I would want: prop up others more than myself.

—

Jovani Hernandez is House of Heatº’s Lead Writer.